Stomach Ulcers: the Hidden Challenge

No horse is completely immune to gastric ulcers, and the numbers are startling. Studies show they affect 37% of pleasure horses, 40% of Western performance horses, and up to 93% of racehorses in training. Even foals aren’t spared, with rates ranging from 20% to 51%, while show and sport horses sit at 54% and 64% respectively.

Endurance horses? They’re at 16% off-season, but that figure can skyrocket to 93% during competition. Diet matters too - ponies fed only hay had zero ulcers, compared to 50% of those on concentrates. Meanwhile, feral horses exhibit the lowest incidence, ranging from 2% to 7%.

These figures tell a clear story: ulcers are common, often silent, and influenced by management choices.

What the surveys reveal about risk factors

Research highlights several management and environmental factors that increase the likelihood of gastric ulcers in horses:

No pasture turnout

Fewer than four meals per day

Intense exercise on limited days

Prolonged stabling

Hard feed and concentrate diets

Stress

Switching from pasture to hay, combined with stall confinement

Lack of direct contact with other horses

Solid barriers instead of rails

Talk radio rather than music in stables

Straw feeding

No access to water in the paddock

Why horses are vulnerable

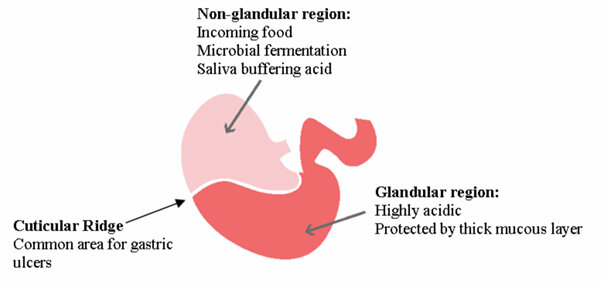

The equine stomach is unique: only half is lined with mucus-secreting cells (the glandular region), while the other half, the non-glandular or squamous region, lacks this protective layer (see Figure 1).

Ulcers can develop in either region, but they are considered distinct disease entities with different causes and treatments. Most ulcers occur in the non-glandular area, where stomach acids and fermentation acids attack unprotected tissue.

Exercise plays a major role: at gaits faster than a walk, abdominal pressure pushes acid into the non-glandular region, causing reflux of bile and intestinal acids into the stomach. In endurance horses, severity correlates directly with ride length.

Ulcers in the glandular area are less common (17–33% in endurance horses, 54–64% in leisure/sport horses, and 47–65% in racehorses), and their exact cause remains unclear.

Figure 1. The equine stomach

Recognising the signs of gastric ulcers

Ulcers are often suspected when horses show any of the following signs:

Poor appetite or picky eating

Weight loss and poor body condition

Chronic diarrhoea

Dull coat

Teeth grinding or belching

Behavioural changes (nervousness, aggression, self-mutilation, crib-biting, wind-sucking, weaving)

Recurrent colic, especially after eating

Reduced performance and exercise tolerance

Abdominal discomfort

Bark and fence chewing

Lying on their back

Loss of vitality

In donkeys, ulcers often present as general dullness and difficulty to manage. However, stomach ulcers are not the only cause of pain behaviour; these signs are not specific and can indicate many other issues that can cause pain (Sykes & Lovett, 2025). A veterinary examination is important.

Interestingly, studies in the USA and UK show that 51% of foals and 84% of yearlings with ulcers display no symptoms at all. And with up to 90% of performance horses affected, it’s no surprise that a wide range of signs has been reported, even watery eyes or frequent whinnying!

The most suggestive indicators are:

Loss of appetite (especially for grain)

Pain after eating

Teeth grinding

Belching

But here’s the challenge: diagnosing ulcers based on symptoms alone is unreliable. None of these signs are unique to ulcers, and even with endoscopic confirmation, symptoms should only be attributed to ulcers if other causes are ruled out and they improve with treatment.

Treatment: Why “No acid, no ulcer” matters

In human medicine, the mantra is simple: no acid, no ulcer. The same applies to horses.

Non-glandular ulcers are typically treated with acid suppressants, such as omeprazole, which is highly effective for this type.

Glandular ulcers, however, respond poorly, with only 25% healing after 28–35 days of omeprazole therapy, compared to 78% of non-glandular ulcers. Alarmingly, 23% of horses experience worsening glandular ulcers after omeprazole treatment.

This highlights the importance of accurate diagnosis and tailored treatment plans.

Feeding and Supplement Strategies for Ulcer Management

Both types of ulcers may benefit from 150–250 ml of corn oil daily, which has been shown to reduce acid production.

Protectants, such as sucralfate, create a barrier over the stomach lining and can help with glandular ulcers when used for at least eight weeks. Other options include pectin–lecithin complexes, which may be suitable in low-to moderate-risk environments. These increase mucus in gastric juice, though they are less effective when ulcers result from prolonged fasting. When combined with an antacid (e.g., magnesium or aluminium hydroxide) and live yeast, outcomes improve for both types of ulcers.

A note on acid-suppressing medications such as omeprazole: calcium absorption is reduced by 15 – 25% in horses on omeprazole, and additional calcium supplementation is required (Pagan et al, 2020). Jenquine Calsorb Forte® and Bone Formula Forte® provide highly bioavailable calcium and complementary nutrients to support optimal bone strength and mineral balance, helping to offset reduced absorption and maintain skeletal health in horses on acid-suppressing medications.

A word of caution on aluminium: While it stimulates mucus secretion and cell growth, long-term use in humans has been linked to intestinal mineral deposits, reduced bone density, and effects on the immune, digestive, and nervous systems. Chronic toxicity can also occur in horses. Before using aluminium-based products, check body aluminium status via hair mineral analysis.

Additional Feed Supplements

To promote a healthy stomach and protect the lining, consider supplements containing:

Dried apple pectin pulp and other fruit fibres

Soy lecithin

Lucerne meal

Insoluble oat fibre (β-glucan)

Polar lipids

Natural antioxidants

Antacids such as calcium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate

These ingredients have been shown in other species to support and protect the stomach lining, maintain normal digestive function, bind bile acids, and reduce damage caused by oxygen-free radicals. In horses, antacids such as calcium carbonate can also help safeguard the non-glandular region from the harmful effects of gastric acids.

References

Pagan J et al (2020) Omeprazole Reduces Calcium Digestibility in Thoroughbred Horses. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 86 March 102851

Sykes B and Lovett A (2025) Can All Behavioral Problems Be Blamed on Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome? Animals 2025, 15(3), 306; https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15030306