Heat Stress & Dehydration in Horses: the Hidden Summer Risks

There’s something irresistible about spending a bright, sunny day in the saddle, whether you’re training, competing, or simply exploring the trails. Yet beneath the pleasant atmosphere lies a very real challenge for horses: the combined impact of heat, humidity, dehydration, and fatigue. Horses produce enormous amounts of heat during exercise, up to sixty times more than at rest, and their ability to release that heat depends entirely on the environment around them. As riders, understanding this delicate balance is essential because even a fit, well‑trained horse can quickly become overwhelmed.

How horses cool themselves

In mild to warm weather, a horse can cool itself efficiently. When the temperature ranges between 20–25°C and the humidity remains low, blood is diverted to the blood vessels in the skin, where heat naturally dissipates into the cooler surrounding air. Sweating adds an extra layer of protection, allowing evaporation to pull heat out of the body. However, this system depends on two crucial factors: the surrounding air must be cooler than the horse’s body, and the air humidity must be low to allow moisture to evaporate from the sweat.

When the air temperature rises to 32°C or higher, the gradient that allows heat to move from the skin to the air disappears. Heat can no longer be transferred into the air, no matter how much blood reaches the skin. At this point, the horse must rely almost exclusively on sweating, but sweating can only help if the moisture evaporates. High humidity prevents evaporation, creating a perilous situation where the horse continues to generate heat internally while losing its ability to cool itself externally. The result is rapid and potentially life-threatening heat load.

A practical way to reduce internal heat production is through dietary management. A high‑oil diet (250–750 ml linseed oil per day) can decrease the heat generated during digestion and reduce heat produced by the muscles during exercise. This reduces the heat load the body needs to dissipate, helping slow the onset of fatigue and supporting the horse’s ability to cope in hot weather.

Which horses are more at risk

Not all horses regulate heat equally. A horse's fitness level plays a major role; an unfit horse produces more heat for the same effort, and its cardiovascular system is less able to support cooling. Younger and older horses, those carrying excess weight, and those with thick coats may struggle even in moderate conditions. Travel adds an additional burden, with horses losing two to three litres of fluid per hour during long journeys. Once they arrive, they may require 24 to 48 hours simply to restore their fluid balance before they can safely work.

Humidity, rough terrain, poorly ventilated floats or stables, and intense warm-ups can all contribute to accelerated overheating. Riders may unintentionally make things harder by working their horses during the hottest part of the day or by underestimating how quickly a horse can reach its thermal limit. Horses transported from cooler climates face an additional problem: they may need two to three weeks to acclimate properly to hot, humid conditions, and until they adapt, their tolerance is significantly reduced.

Dehydration: why water alone isn't enough

When a horse sweats, it loses far more than water. Sweat contains sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium and magnesium, minerals that are essential for nerve function, muscle contraction, and the body’s thirst response. As these electrolytes become depleted, the horse may actually lose the desire to drink, even when dangerously dehydrated.

Dehydration affects performance long before it becomes a crisis. A fluid loss of just 2-3% can reduce a horse’s capacity for work by 10%. More severe imbalances may lead to conditions like thumps (synchronous diaphragmatic flutter), where the diaphragm spasms in time with the heartbeat, or puffs, where panting becomes uncontrolled. Both issues arise from disruptions in the availability of calcium and potassium. Without restoring electrolytes, not just water, these problems can worsen rapidly.

For horses working regularly in hot weather, daily electrolyte supplementation is essential. Horses consuming mostly hay usually receive ample potassium but may be deficient in sodium, chloride, and sometimes calcium or magnesium. Providing salt twice a day and adjusting the quantity during hotter periods can help support normal hydration and cooling. For horses who are fussy about anything added to their feed, there is also a hydration snack cookie you can try, a homemade treat that disguises electrolytes in a more appealing form. You can find the recipe here.

If electrolyte losses during heavy sweating aren’t replaced promptly, the consequences can go far beyond simple fatigue. Horses can develop conditions such as thumps, puffs, and even tying‑up, all of which can escalate quickly into medical emergencies. Thumps, properly known as Synchronous Diaphragmatic Flutter (SDF), occur when the diaphragm begins to contract in rhythm with the heartbeat. This creates a visible jerking of the flanks that almost resembles hiccups, and it is strongly associated with low blood calcium levels. Thumps often appear during rest breaks or recovery periods, especially if a horse has been allowed to drink large volumes of water without receiving appropriate electrolytes. This dilutes blood calcium and potassium even further, worsening the problem instead of relieving it.

Puffs reflect a different disturbance, where panting becomes exaggerated or uncontrollable because the horse can no longer regulate its respiratory rate effectively under heat load. Tying‑up, meanwhile, involves painful muscle cramping and stiffness linked not only to electrolyte deficiencies but also to low levels of key vitamins and minerals or diets too rich in grain. Magnesium, like calcium, is lost in significant amounts through sweat, and horses performing moderate to intense work may need to double their magnesium intake to maintain normal muscle function. Together, these conditions illustrate why preventing dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and overheating is not just good management; it is critical to the horse’s safety and well-being.

Recognising the signs of heat stress and dehydration

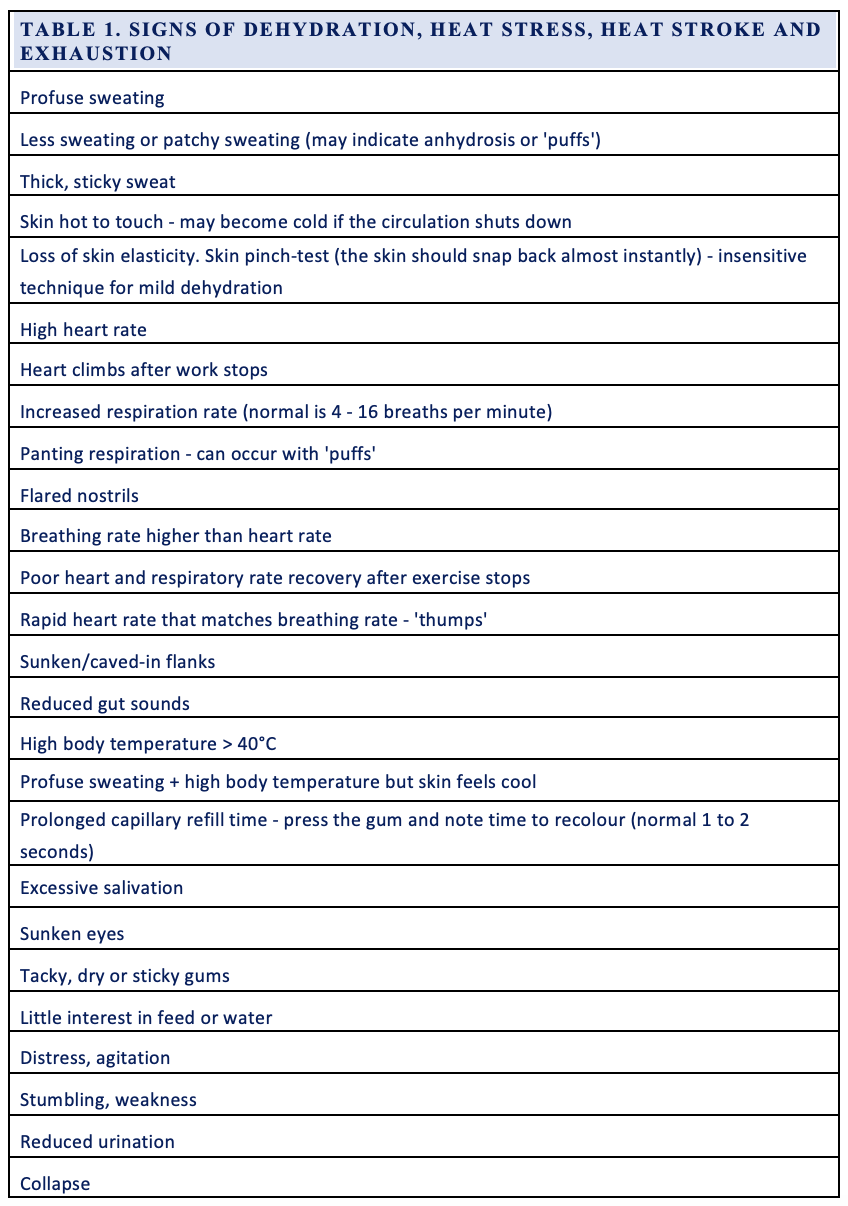

Heat stress and dehydration often begin subtly, and the early signs are easy to overlook, especially on hot summer days when sweating and heavy breathing might seem normal. A horse may start by sweating heavily, or just as concerning, may sweat less or only in patches. Breathing may become faster, the nostrils flare, and the horse may appear dull, agitated, unusually tired, or slightly uncoordinated. As heat load builds, heart rate stays elevated even after exercise stops, and the gums may become tacky, dry, or slower to refill with colour.

Because every horse responds differently to heat and humidity, these early changes can be mistaken for simple fatigue. But once a horse’s body temperature rises above 40°C, the risk of collapse, heat stroke, and organ damage increases rapidly. Knowing what is normal for your horse, its attitude, sweating pattern, breathing, and recovery times, is one of the most powerful tools you have. Even small deviations can be the first warning that something is going wrong.

Heat stress, dehydration, and overheating can progress quickly, and recognising the warning signs early is critical. The following list outlines the key clinical signs associated with dehydration, heat stress, heat stroke, and exhaustion. Some begin subtly, while others signal an immediate emergency. Becoming familiar with these signs will help you detect problems early and act before the horse’s condition deteriorates (see Table 1).

Effective cooling: what science tells us works best

Cooling a horse effectively and quickly can be life-saving. The evidence is clear: continuous application of cold water is the most efficient method. Instead of applying water and scraping it off repeatedly, simply continue hosing or pouring cold water over the entire body, focusing on the large veins of the neck, inner thighs, and lower limbs. As fresh cold water replaces the water warming on the skin, heat is steadily drawn away.

Removing tack immediately, walking the horse slowly, and offering small drinks of cool water all help support recovery. Avoid towels, coolers, or any fabric that traps heat against the skin. Shade and airflow are also essential. Small details matter, such as planning rides during the cooler parts of the day, reducing unnecessary tack, clipping heavy coats, and using fly protection to minimise energy lost to stomping or pacing.

Acclimation, conditioning & prevention

Horses cope best with heat when they are fit, well‑conditioned, and gradually exposed to warmer weather. A horse brought from a cool climate into a hot, humid environment requires time for its sweating mechanism and circulatory response to adjust. During this acclimation period, even mild exertion may stress the horse more than expected.

Conditioning should progress slowly, allowing the horse’s cardiovascular and muscular systems to adapt. Careful attention during training, monitoring heart rate, breathing, and recovery times, can offer early clues about how well the horse is managing heat. Riders should also be aware that excessive warm‑ups can push a horse into heat load before the main work even begins, especially if the humidity is high.

When heat becomes an emergency

If a horse shows signs of severe heat stress, including confusion, weakness, staggering, extreme sweating or lack of sweating, or rapid breathing that worsens after exercise, the situation can deteriorate quickly. The priority is to cool the horse immediately while contacting a veterinarian. Rapid cooling, continuous cold water, slow walking, and attentive monitoring may be the difference between recovery and a medical emergency. If the horse’s condition does not improve quickly, intravenous fluids and electrolyte therapy may be required.

Conclusion

Summer riding can be one of the great pleasures of horse ownership, but it requires a heightened awareness of how horses respond to heat and humidity. By understanding the physiology of heat load, recognising early signs of distress, implementing hydration and electrolyte strategies, and cooling horses using scientifically proven methods, riders can minimise risk and keep their horses healthy and comfortable even on the hottest days. With thoughtful preparation and attentive care, you and your horse can enjoy the season safely and make the most of every summer ride.

Dr Jennifer Stewart

BVSc BSc PhD Equine Veterinarian and Consultant Nutritionist